Scouting — The Steering Wheel

go.ncsu.edu/readext?297948

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Getting Direction from Scouting

Recommendations for pest control are based on accurate field scouting. Without knowing what pests you have, it is impossible to know if, when, or with what you need to treat. Therefore, scouting drives the direction for pest control.

Recommendations for pest control are based on accurate field scouting. Without knowing what pests you have, it is impossible to know if, when, or with what you need to treat. Therefore, scouting drives the direction for pest control.

There is no one pesticide or combination of pesticides that will keep trees pest free. All pesticide applications have a cost — not just the cost of the material(s), but also the impact on natural predators and risks to environmental and human health. Often the best pest control is to do nothing at all, but you can safely do this only by accurately knowing what pests and predators are in your trees.

What is Scouting?

Scouting is the regular, systematic, and repeated sampling of pests in the field in order to estimate the presence of a pest and their population levels. Scouting is geared towards the major pest problems and is modified by weather that favors particular pests. In order for scouting to happen, you have to make time for it, just like you would for any other production practice. As you get more familiar with each field and learn where pest problems are found, scouting should take less and less of your time.

Part of scouting is to determine if certain pests such as elongate hemlock scale, balsam woolly adelgid or rosette buds are present at all in the field. Once you know these pests are present, scouting is needed to determine if enough trees are affected to warrant an insecticide application. For other pests which reproduce and spread more quickly such as twig aphids, Cinara aphids, spider mites and rust mites, scouting is needed to keep track of numbers so that the population doesn’t build to a level where it causes economic damage. While scouting, not only pests but natural predators are observed which should also be factored into the decision whether or not to treat. Once a pesticide has been applied, scouting is used to determine how well treatments worked.

Scouting is also important for ground cover management. Fields need to be thoroughly scouted to determine the presence of hard to control weeds, especially around field edges where such problems can get a foothold. Field observations of weed growth and regrowth are also important for timing of chemical suppression.

Scouting Tools

It doesn’t take a great deal of equipment to do a good job of scouting. The following tools are useful in scouting though not all are absolutely necessary:

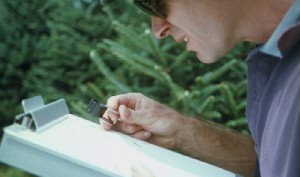

It doesn’t take a great deal of equipment to do a good job of scouting. The following tools are useful in scouting though not all are absolutely necessary:- A good quality magnifying lens with at least 7X power that you can see pests clearly with.

- White plastic plate or something similar to beat the foliage over.

- Flagging to mark problem trees. This should be of a color that is not used in tagging trees.

- Pocket knife to cut off bark samples.

- Clippers to cut off shoots and branches.

- Plastic bags to collect samples in.

- Marker to write on plastic bags the location and date when sample was taken.

- Camera to take photographs of problems. A cell phone camera may be adequate.

- GPS unit to mark location of problem areas so maps can be developed — again many phones have this feature.

- Map of the field so that problems can be recorded.

- Scouting form so that scouting results can be recorded.

- Shovel for digging in the soil to find grubs or other root problems.

- Soil sample probe, bucket and boxes to determine fertility needs.

Scouting Calendar for Pests

The following is a sample scouting calendar that takes into account when pest problems are easiest to identify. This calendar should be modified depending on your location, what pests you have, and the weather. For instance, when the weather is hot and dry, spider mites in particular are more of a problem. Weed composition and height should be observed during all scouting trips.

- March/April: In March and April, pests become active. Twig aphid eggss start to hatch by mid-March. Depending on the weather, rust mites and spider mites also start to hatch. The balsam woolly adelgid molts from the overwintering nymph to the adult and may start to lay eggs. During this time frame, it is important to determine the presence and activity of twig aphids and mites to determine if controls are required before budbreak.

- May: The time right up until budbreak and right after budbreak is important to further monitor twig aphids and mites. Predators are becoming more active and may be found on trees or in ground covers.

- June/July: During June and July, spider mites may flare up if it is dry. The elongate hemlock scale males mature and produce the protective white fuzz that can be easily seen on foliage.

- August through October: Once tree tops straighten, balsam woolly adelgid can be scouted for by examining trees with crooked tops for the insect. The elongate hemlock scale will have another flush of growth that can be monitored. Rosette buds are clearly formed and the presence and prevalence of this pest can be followed. If it is dry, spider mites can become a problem again. Also be on the look-out for Cinara aphids in trees to be harvested. Early fall is also the time to dig in the soil looking for white grubs.

A scout also typically takes soil and plant tissue samples to determine fertility. Soil samples are best taken in the fall to determine fertilizer use for the following year.

The number of scouting trips required per year will change over time. Younger trees need scouting less as many of the pest problems are only an issue as trees near harvest. In fields with few pest problems, you may only need to visit a couple of times a year. In other fields where mites are an issue, you might need to revisit a field seven or eight times. A good scout will concentrate their scouting efforts based on prior experience with each field.

How to Look for Pests

The following techniques are useful in finding pest problems.

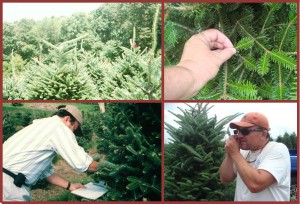

The following techniques are useful in finding pest problems.- Spotting tree symptoms. Tree symptoms of pest damage can be seen from many rows away. Be on the look-out for trees with crooked tops, dead branches, yellow or spotted foliage, white to grayish discoloration of the needles, or needle drop. Look for discolored needles back in the canopy in the lower half of the tree. Walk to suspect trees and examine the foliage to determine the cause of problems.

- Beating foliage. Hitting foliage forcibly with your hand over something like a white plastic plate will dislodge many pests and predators. This is the best way to monitor twig aphids and to find beneficial insects. Other pests that can be dislodged in this fashion are elongate hemlock scale adults and crawlers, spider mites, and rust mites. Be sure to use a magnifying lens to correctly identify insects.

- Picking a shoot. Some pest either can’t be dislodged from foliage or are found at lower numbers by examining tree shoots. Pick a small shoot of the most current growth from back in the canopy of the tree and look on both sides for mites, scales, twig aphid eggs, and woolly adelgid. Sometimes predators are also found in this way, especially predatory mites. To observe scales, look on the underside of foliage, and remove a branch with 2-3 year’s worth of growth. Look especially for parasitized scales indicated by a round hole in the center of female (brown) scales.

- Examining the bark. To find balsam woolly adelgid, examine the trunk of the tree and along the underside of branches. Cut-off suspect woolly spots with a pocketknife to look at them more closely with a magnifying lens.

- Digging in the soil. Some pests such as white grubs can only be found by digging in the soil. If a tree is stunted or dying, it is also a good idea to dig up roots to examine their condition. Root aphids can be found in this manner as well as roots infected with Phytophthora root rot or fed upon by grubs.

Writing Scouting Results

Keeping a written, systematic record of scouting results is key to incorporating scouting and IPM into your production practices. Records can take on many forms — everything from a large calendar where observations are noted, to a small notebook where journal entries are written, to computer spreadsheets. It doesn’t matter how you keep records of scouting, just so you do.